In the mid-forties, the painting by Jackson Pollock (1912-1956) constitutes a halfway state between easel painting and murals. American visual art critic Clement Greenberg (1909-1994) promptly noticed, speaking of a crisis of easel painting, and, in the wake of it, Pollock stated

“I intend to paint large movable pictures which will function between the easel and the mural (…) I believe the easel picture to be a dying form, and the tendency of modern feeling is towards the wall picture or mural. I believe the time is not yet ripe for a full transition from easel to mural. The pictures I contemplated painting would constitute a halfway state and an attempt to point out the direction of the future, without arriving there completely”.

The large-scale assumes, progressively, decisive importance for Pollock, but it is a really different notion of monumentality from the European one.

Consider that Monet’s Water Lilies paintings began to be appreciated for their “greatness” of size, only by a comparison with 1950s and 1960s American art, characterized by a large-scale environmental projects. The latter element, involves the viewer as he experiences a different existential spatiality. In other words, such monumentality aspires to influence the physical space, aspires towards a timeless dimension: it is a proposal to live life through art.

In fact, the greatly expanded size of the Abstract Expressionists’ canvases soar to epic heights, as repeatedly highlighted by both critics and artists; just think of Barnett Newman’s words: “The basic issue for a work of art, whether it’s architecture, painting or sculpture is first and foremost for it to create a sense of place”.

So, back to 1945-7. Crucial years for Pollock: in 1945 he married the artist Lee Krasner, and in November, the couple moved out of town, to find a higher concentration,

to Springs in East Hampton (Long Island).

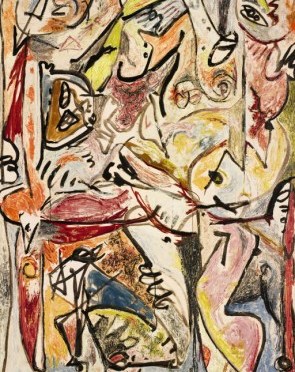

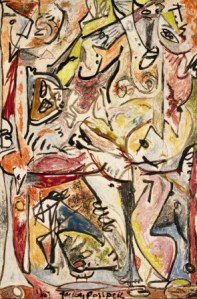

Two series are the 1946’s fruits: The Accabonac Creek and The Sounds in the Grass. The two series move away from those structures we find in the Guardians of the secret.

Very important, in this sense, “Sounds in the grass” (1946), consisting of seven paintings, is a significant step towards the creative freedom and the artist’s freely poured paintings of 1947-8’.

His body’s forces on the canvas, the sweeping brush strokes, become a gesture of liberation.

“Hence Pollock conveys a feeling of passion and visceral intensity playing between literal surface and illusionistic depth, creating a tension between surface and background”.

Yet, we find symbols and surrealist elements, with clear reference to Miro, but Pollock is achieving his own personal style.

The titles are evocative and enigmatic, “conventional” would have said Lee Krasner, while, in reality, they refer to the Surrealist art movement. Moreover, they recall a primeval natural world, as well as the man’s hidden nature (his shadow-side). Pollock himself, a few years later would have confirmed:

“The unconscious is a very important side of modern art and I think the unconscious drives do mean a lot in looking at paintings”.

His method of paint application still follows the “traditional way”, i.e. through the “contact” with the canvas, and yet Pollock no longer applies a color with a brush, but often squeeze it directly from the tube onto the canvas, pushing and spreading it with blunt tools, to create a thick, irregular crust. A canvas which moreover is no longer on the easel, but unstretched on the studio floor.

The Blue Unconscious

Shimmering substance

Earth Worms

Eyes in the Heat

Croacking Movement

Something of the Past

The Dancers

Sounds in the grass were exhibited with Accabonac Creek, in January 1947 at the Peggy Guggenheim’s gallery, Art of This Century. (2) On this occasion Clement Greenberg wrote

“Jackson Pollock’s fourth one-man show in so many years at the Art of this Century is the best since his first one and signals what may be a major step in his development-which I regard as the most important so far of the younger generation of American painters. He has now largely abandoned his customary heavy black-and-whitish or gun-metal chiaroscuro for the higher scales, for alizarins, cream-whites, cerulean blues, pinks, sharp greens. (…) Pollock has gone beyond the stage where he needs to make his poetry explicit in ideographs. What he invents instead has perhaps, in its very abstractness and absence of assignable definition, a more reverberating meaning. He is an American and rougher and more brutal, but he is also completer. (…) Pollock points a way beyond the easel, beyond the mobile, framed picture, to the mural perhaps, or perhaps not. I cannot tell”. (3)

Well, although Greenberg sometimes uses Cubism, the post-Picasso generation and Dubuffet’s abstract works to explain what was happening in Pollock’s work, it is remarkable that he has identified a deep revolution in his research, the crisis of easel painting, and a new “way beyond (…) perhaps to the mural, or perhaps not”.

Now, it is in such “or perhaps not” we find the radical change, but also the originality of Pollock when comparing his canvases to the murals (and their political and social contents). With Pollock, painting becomes an immersive experience, a statement of faith in art and, far from any destructive intention, the everlasting search for existential authenticity.

(1) Jackson Pollock, Application for Guggenheim Fellowship, 1947, in Pepe Karmel (ed), Jackson Pollock: Interviews, Articles, and Reviews; p 17, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1999.

(2) Art of This Century, New York. Jackson Pollock. January 14–February 1, 1947. Exhibited Croaking Movement, Shimmering Substance, Eyes in the Heat, Earth Worms, The Blue Unconscious, Something of the Past, The Dancers, The Water Bull, Yellow Triangle, Bird Effort, Gray Center, The Key, Constellation, The Tea Cup, Magic Light, Mural. [Catalogue, with two paragraph preface by N. M. Davis.]

(3) Clement Greenberg, article in The Nation, February, 1, 1947

Interview to Clement Greenberg

Pollock by Hans Namuth

Bibliography

http://research.moma.org/jpbib/JPbibliography.htm

JACKSON POLLOCK, SOUNDS IN THE GRASS

Alla metà degli anni Quaranta, la pittura di Jackson Pollock (1912-1956) è a metà strada tra la pittura di cavalletto e il murales. Lo aveva già notato l’influente critico americano Clement Greenberg (1909-1994), che giustamente parlava di crisi di pittura da cavalletto, e, sulla stessa scia (probabilmente sotto “dettatura” di Greenberg stesso) lo dichiarò Pollock stesso:

“È mia intenzione dipingere quadri di grandi dimensioni, mobili, a metà strada tra l’opera da cavalletto e il murale (…) Sono convinto che la pittura da cavalletto sia una forma morente, e che la tendenza del sentire contemporaneo sia orientata verso la pittura su parete o i murales. Credo che i tempi non siano ancora maturi per il passaggio definitivo dal cavalletto al murales. Le immagini che mi propongo di dipingere costituirebbero uno stadio intermedio e un tentativo di indicare la direzione del futuro, senza tuttavia arrivarvi completamente”. (1)

La scala assume, con il passare del tempo, un’importanza decisiva per Pollock, ma si tratta di una nozione di monumentalità molto diversa da quella europea.

Basti pensare che le Ninfee di Monet iniziarono ad essere apprezzate per la loro “grandiosità” soltanto dopo il paragone con opere americane degli anni Cinquanta, caratterizzate da una scala addirittura “ambientale”. Quest’ultimo elemento, fa sì che lo spettatore percepisca una spazialità esistenziale diversa. In altre parole, questa dimensione aspira a condizionare lo spazio fisico, a catturare l’osservatore: è quasi una proposta a esperire la vita attraverso l’arte.

Infatti, la grande dimensione degli espressionisti astratti ha un’epicità più volte evidenziata sia dai critici sia dagli artisti, basti pensare alla frase di Barnett Newman: “La questione fondamentale per un’opera d’arte, che si tratti di architettura, di pittura o di scultura, è soprattutto creare il senso di un luogo”.

Ma torniamo al 1945. Sono anni cruciali per Pollock che in quell’anno si sposa con l’artista Lee Krasner e, a novembre, si trasferisce fuori città per trovare una maggiore concentrazione.

La coppia si stabilisce a Springs nell’East Hampton (Long Island)

Le creazioni di questo periodo mostrano un allontanarsi da quelle strutture che troviamo nei Guardiani del segreto. La pennellata si libera, acquisendo una forza gestuale più incisiva. Si crea un rapporto di tensione tra scritture superficiali ed elementi in secondo piano che, progressivamente, perdono ordine. Troviamo ancora simboli ed elementi surrealisti, con chiaro riferimento a Mirò, ma ormai Pollock si sta svincolando del tutto, per approdare ad una cifra stilistica personale.

Fondamentale, in questo senso, la serie “Sounds in the grass” (1946) composta da sette dipinti che rappresentano una svolta importante verso la libertà creativa degli anni cruciali 1947-8.

I titoli sono evocativi ed enigmatici, “convenzionali” avrebbe detto Lee Krasner, ma in realtà richiamano ancora l’entourage artistico surrealista. Del resto, rinviano ad un mondo naturale primordiale, così come al lato più oscuro, primigenio dell’uomo. Pollock stesso, qualche anno più tardi avrebbe affermato: L’inconscio è un aspetto molto importante dell’arte moderna e penso che l’inconscio davvero significhi molto nell’osservazione dei dipinti.

Opere eseguite ancora in modo “tradizionale” cioè attraverso il “contatto” con la tela, e tuttavia Pollock non applica più il colore con il pennello, ma spesso lo spreme direttamente dal tubetto sulla tela, spingendolo e spargendolo con arnesi smussati, per creare una crosta spessa e irregolare. Una tela che oltretutto non è più sul cavalletto, ma stesa a terra.

The Blue Unconscious (oil on canvas 84 x 56 inch. 213.4 x 142.1 cm)

Shimmering substance

Earth Worms

Eyes in the Heat

Croacking movement

Something of the Past

The Dancers

Qui si acuisce il problema della costruttività con il colore. Infatti, si delinea ora la tendenza che avrà come esito uno scontro tra pennellata e muro di materia, in quanto il grafismo, combinato con l’elemento materico, pone una serie di problemi e formali e tecnici che Pollock risolverà con il dripping.

Sounds in the grass venne esposta insieme alla serie, di poco precedente, Accabonac Creek nel gennaio 1947 presso la galleria di Peggy Guggenheim Art of This Century. (2) E proprio in questa occasione Clement Greenberg scrisse:

“La quarta mostra personale di Jackson Pollock in tanti anni alla galleria Art of This Century è la migliore dall’esordio e segna quello che potrebbe essere un passo importante nel suo iter, che considero il più importante finora della generazione più giovane di pittori americani. Ha in gran parte abbandonato il suo abituale forte chiaroscuro in bianco e biancastro o canna di fucile per le scale più alte, per i rossi di alizarina, i bianco-crema, gli azzurri cerulei, i rosa, i verde acido. (…) Pollock ha superato la fase in cui sentiva l’esigenza di esplicitare la propria poetica attraverso degli ideogrammi. Ciò che egli inventa invece è forse, nella sua astrattezza e assenza di una definizione assegnabile, un significato di maggiore eco. Lui è un americano più ruvido e brutale magari, ma anche più completo.

Pollock inaugura il superamento delle pittura da cavalletto, del “mobile”, del dipinto incorniciato, fino al murales forse, o forse no. Non saprei dire”.

Nonostante qui Greenberg si serva di riferimenti al Cubismo, alla generazione post-Picasso e all’astrattismo di Dubuffet per spiegare i mutamenti dell’arte di Pollock, è notevole che abbia individuato una profonda rivoluzione nella sua ricerca volta a tracciare una via oltre il cavalletto, oltre il “mobile”, oltre il dipinto incorniciato “fino al murales forse, o forse no”.

Ora, proprio in quel “o forse no” si esprime la novità, ma anche l’unicità di Pollock rispetto al murales (e ai relativi contenuti politici e sociali): con Pollock la pittura diventa un’esperienza coinvolgente, una dichiarazione di fiducia totale nella stessa e, lungi da qualsiasi volontà demistificatoria, la perenne ricerca di un’autenticità esistenziale. (3)

(1) Jackson Pollock, Application for Guggenheim Fellowship, 1947, in Pepe Karmel (ed), Jackson Pollock: Interviews, Articles, and Reviews; p 17, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1999.

(2) Art of This Century, New York. Jackson Pollock. January 14–February 1, 1947. Vennero esposti Croaking Movement, Shimmering Substance, Eyes in the Heat, Earth Worms, The Blue Unconscious, Something of the Past, The Dancers, The Water Bull, Yellow Triangle, Bird Effort, Gray Center, The Key, Constellation, The Tea Cup, Magic Light, Mural. [Catalogo, con prefazione di N. M. Davis.]

(3) Clement Greenberg, articolo in The Nation, February, 1, 1947

Intervista a Clement Greenberg

Pollock di Hans Namuth

Bibliografia

http://research.moma.org/jpbib/JPbibliography.htm