An intimate, melancholy stylistic hallmark, a kind of apathetic weakness, here is the male image that Willem de Kooning painted in the late thirties.

Leaving behind the geometric abstractions, so popular in the New York scene of the time, the artist created, between 1937 and 1944, a series of male figures who are almost unique in his artworks.

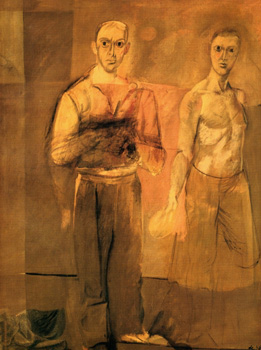

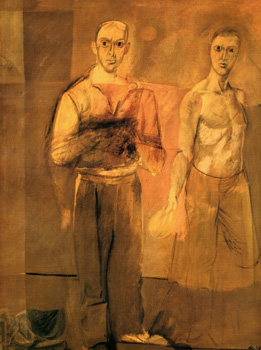

Man (1939) as well as the 1942 Man Standing are apparitions on the threshold between something and nothing

“Since the first evidences, de Kooning proves not to keep the syntax, though veiled and involved in a hot biomorphism, but to practice the path of discord, injecting a kind of poisonous bitterness despite the apparent sensitivity of the compositions. It is a guiding principle, which is important to the extent that as to identify the work sharply compared to Gorky’s goals: the conflict, the repulsion between the parts, instead of harmony between them. “(…)

In Two men standing (1938), in Seated figure (classical male, 1940), andin The glazier (1940),” the figures are as diaphanous apparitions: the air passes through them, they have no weight. What emerges is a sense of incompleteness, between transparency and repentance (see the right arm of the two men standing: as a photographer doesn’t focus his lens on a subject), de Kooning leaves the shapes in a temporary stage: coming into being, will they drop in a tangible “here and now” or will they remain as a Matissian evanescence, as Ingresian archetypes? Despite all this, the faces appear well-delineated, even if not resolved: eyeballs and eyebrows arches are elements of sudden hardening, in the style of Picasso, and in clear agreement with Gorky’s ones; as well as convergence between the two, we can talk about the backgrounds, admittedly flats, at most divided in chromatic areas, but without setting a thickness of space.” (1)

This passage refers to Ingres and Picasso. Why?

A brief clarification is needed.

Just as Picasso, deeply known, understood and loved by Gorky, he was responsible for the revival of the works of nineteenth-century master, from Turkish bath to La Grande Odalisque.

In other words, the recovery of Ingres’ subjects in the twentieth century starts from the centrality given to him by Picasso, after having enjoyed an exhibition in 1905: in fact it is clear the inspiration exerted by the Turkish bath on Demoiselles d’Avignon.

Moreover, Gorky deep admirer of the Iberian artist, long followed, to the letter, a statement on his eclectic inspiration: “The painter is a collector who wants to gather a collection by painting himself the pictures he admires in others’ collections” (“Qu’est-ce que, au fond, un peintre ? C’est un collectionneur qui veut se constituer une collection en faisant lui-même les tableaux qu’il aime chez les autres”). (2)

Now, such really penetrating discussion about the problems of the great masters of painting, made Gorky and his “initiation” to the modern art very “authoritative” in the eyes of friends, first of all de Kooning.

The reason is well known: different essays have painstakingly reconstructed the period in the late thirties while Gorky and de Kooning were sharing the studio, highlighting the intense intellectual exchange between the two. The obsessive focus of the Armenian painter for some artists and his influence on the young Dutchman were admitted by the de Kooning himself that, for this reason, called his friend “the boss”.

For Gorky the strenuous formal investigations of Cézanne, Ingres, Picasso, and Mirò could create something new: his philosophy was innovation through imitation.

Melvin Lader has suggested that Gorky had pushed his friend to adopt different techniques typically after the manner of Ingres, to address and solve some problems in the formal rendering of the figures. (3)

Seated man clearly recalls the 1805 Ingres’s painting Portrait of M. Philibert Riviere in the uncomfortable pose and in the position of the cropped and crossed legs.

“Often based on self-portrait made from photographs and mirrors in his studio, a manikin he constructed and studies of his friends and neighbors, such as poet and dance critic Edwin Denby and photographer Rudolph Burckhardt, they are anonymous, somber and isolated. They are painted in deep, warm tones with indefinite outlines and combine allusions to art history, modernism, and everyday life. Prompted in part by Gorky’s contemporaneous figure paintings, de Kooning later referred to the men as imaginary portraits in the Manner of Ingres and Le Nain brothers.” (Selden Roadman, Conversations with artists 1961 p 103). (4)

Surprise! We find in Two standing men and in Portrait of Rudolph Burckhardt a reference to Le Nain brothers paintings: particularly, in depicting the folds of the trousers.

Art critic Jed Perl, in a section called “The Philosopher King” of his interesting New Art City: Manhattan at Mid-Century, expands on de Kooning’s artwork, pointing out the influence of Le Nain brothers, usually less storied than that of other ones.

Different set of problems arises if we consider “Men’s” physiognomy: in fact, it is in Cézanne’s late portraits we can find the same lonely, detached facial expression that belongs to de Kooning’s Men.

“Although he was definitely exposed to Cézanne at an earlier date, direct influence does not come into play in de Kooning’s paintings until about 1938, during his friendship with Gorky. Clear examples of this influence can be found in his paintings Two Men Standing (figure 5) of 1938 and in Glazier of 1940 (figure 6). The folds of the pant leg in the man standing on the left of Two Men Standing show a noticeable attempt to both flatten the picture plane and to show depth at the same time, while the men’s chests are similarly modeled using flat planes of color. Cézanne’s influence is even more obvious in Glazier: the use of flat planes of color are used to render the folds of the tablecloth and creases in the pants of the figure”. (5)

Once he described Glazier’s creation.

“I took my trousers, my work clothes. I made a mixture out of glue and water, dipped the pants in and dried them in front of the heater, and then of course I had to get out of them. I took them off—the pants looked so pathetic. I was so moved; I saw myself standing there. I felt so sorry for myself. Then I found a pair of shoes—from an excavation—they were covered with concrete, and put them under it. It looked so tragic that I was overcome with self-pity. Then I put on a jacket, and gloves. I made a little plaster head. I made drawings from it, and had it for years in my studio.” (6)

De Kooning does not look for the Sublime, on the contrary, he’s always in touch with the material world. That explains his openness to kitsch and popular culture.

“Art never seems to make me peaceful or pure. I always seem to be wrapped in the melodrama of vulgarity. I do not think.. ..of art as a situation of comfort”. (7)

Many years later de Kooning would have called this period back to mind.

“I destroyed almost all those paintings,” de Kooning later told Selden Rodman. “I wish I hadn’t. I was so modest then that I was vain. Some of them were good, a part of the real me. Just as Van Gogh’s Potato Eaters [a great early painting of a family of peasants] is good, as good as anything he painted later in the true Van Gogh style.” The paintings that survived from the period did so mostly by chance: they were bought and removed from the studio before he destroyed them.”(8)

Such a sentence explains his obsession with making and unmaking the painting, his personality “under the sign of light-fingered Mercury”, being the artist ambitious to identify himself with the mysterious and brooding Saturn, just as Jed Perl clarified:

“Willem de Kooning emerges (…) as the archetypal modern urban man. He is by turns swaggering and sensitive. He is neurotic, self-assured, vehement, mercurial. He is a seeker, a striver, a comedian, a seducer, a dreamer. This quick-change personality comes through first of all in the splendid variety of de Kooning’s brushwork, which in a single painting can range from the elegant to the offhand, from delicate traceries to slashing strokes. You feel the artist’s variety in the conundrums that are his compositions: sometimes oppressively maze-like, sometimes disorientingly open-ended, often designed to deny any resolution. And you see constant change in the way his work shifts, even within a brief period, from a focus on the figure to a more strenuously abstracted figure or a suggestion of a landscape. De Kooning is a man who makes up his mind and then unmakes it, over and over again”. (9)

(1)Roberto Pasini L’Informale. Stati Uniti Europa Italia. Clueb Bologna 1995 p.103

(2)Quoted by Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, german art dealer, art collector, publisher and writer in Huit entretiens avec Picasso, Le Point, Mulhouse, n° XLII, oct. 1952, p. 22-30

(3) Melvin Lader, P. Graham, Gorky, de Kooning, and the ‘Ingres Revival’ in America. Arts Magazine. 52, no.7 (March 1978), p.94-99.

(4)SusanF.Lake, Willem de Kooning: The Artist’s Materials p.8

(5) Hayden Herrera. Arshile Gorky: His Life and Works. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York: 2003 p.138 quoted in Lauren Foster, Arshile Gorky’s Influence on the Early Paintings of Willem de Kooning Senior thesis, 2006, MontclairStateUniversity

(6) Sally Yard , Willem de Kooning: Works, Writings and Interviews, July 1st 2007, Ediciones Poligrafa S.A. p.21

(7) Robert Motherwell, Beyond the Aesthetic, Design 47, April 1946, as quoted in W.C, Seitz Abstract Expressionist Painting in America, Cambridge Massachusetts, 1983, p.101

(8) Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan. de Kooning: An American Master. New York, Knopf, 2004, p.141

(9) Jed Perl “The Abstract Imperfect” in The New Republic, November 3, 2011

………………………………………………………………………………………

GLI UOMINI DI dE KOONING

Una cifra intima, malinconica, una sorta di apatica debolezza: ecco le figure maschili che Willem de Kooning (1904-1997) dipinge alla fine degli anni Trenta.

Lasciandosi alle spalle le astrazioni geometriche, così in voga nel panorama newyorkese del tempo, l’artista realizzò, tra il 1937 e il 1944, una serie di figure maschili che rappresentano quasi un unicum nel suo corpus.

Man (1939) così come Standing Man (1942) sono presenze sulla soglia tra qualcosa e il nulla.

“Fin dalle prime prove de Kooning dimostra di non tenere alla sintassi, anche se velata e coinvolta in un caldo biomorfismo, ma di praticare la strada della disarmonia, iniettando una sorta di velenosa asprezza pur nella apparente delicatezza delle composizioni. È un principio-guida, importante al punto da contraddistinguerne l’opera in maniera netta rispetto ai traguardi di Gorky: il dissidio, la repulsione fra le parti, invece dell’amore fra di esse”. (…) In Two standing men, in Seated figure, e in The glass-maker “le figure sono diafane come apparizioni: l’aria le attraversa, non hanno peso. Ne emerge un senso di incompletezza, fra trasparenza e pentimenti (si veda il braccio destro dei due uomini in piedi: come un fotografo che non metta a fuoco il suo obiettivo, de Kooning lascia le forme in uno stadio provvisorio: prenderanno corpo, si caleranno in un “qui e ora” tangibile, o resteranno matissiane evanescenze, archetipi ingresiani? Ad onta di tutto questo, i volti appaiono più decisi, se non più risolti: globi oculari e arcate cigliari sono nuclei di improvviso rassodamento, di picassiana memoria, in chiara sintonia con Gorky; così come di convergenza fra i due si può parlare anche a proposito degli sfondi, dichiaratamente piatti, al massimo sezionati per aree cromatiche, ma privi di ambientazione, di spessore spaziale.” (1)

In questo brano si fa riferimento a Ingres e Picasso. Perché?

Una breve precisazione è necessaria. Proprio a Picasso, profondamente conosciuto, compreso e amato da Gorky, si deve la ripresa e il successo di opere del maestro ottocentesco, a partire dal Bagno turco e La Grande Odalisque.

In altre parole, il recupero di motivi ingresiani nel Novecento nasce dalla centralità donatagli da Picasso subito dopo averlo apprezzato ad una mostra nel 1905: basti pensare all’ispirazione esercitata dal Bagno turco sulle Demoiselles d’Avignon.

Del resto, Gorky profondo ammiratore dell’artista iberico, per molto tempo ne seguì, alla lettera, un’affermazione sulla propria ispirazione eclettica: “Il pittore è un collezionista che vuol farsi una collezione dipingendo lui stesso i quadri che gli piacciono in casa d’altri”.

(“Qu’est-ce que, au fond, un peintre ? C’est un collectionneur qui veut se constituer une collection en faisant lui-même les tableaux qu’il aime chez les autres” citato da Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler) (2).

Ora, proprio questa penetrante riflessione sui problemi pittorici dei grandi maestri rendeva Gorky e la sua “iniziazione” all’arte moderna molto “autorevole” agli occhi degli amici, primo fra tutti de Kooning.

.Il perché è noto: molti studi hanno puntigliosamente ricostruito il periodo di condivisione dell’atelier di Gorky e de Kooning nei tardi anni Trenta, evidenziando l’intenso scambio intellettuale tra i due. L’attenzione ossessiva del pittore armeno per alcuni artisti e il suo influsso sul coetaneo olandese sono stati ammessi dallo stesso de Kooning che, proprio per questo, aveva soprannominato l’amico “the boss”.

Per Gorky, infatti, l’inesauribile imitazione di Cézanne, Ingres, Picasso e Mirò avrebbe potuto condurlo a profonde novità stilistiche.

Melvin Lader ha suggerito l’ipotesi che Gorky avesse spinto l’amico ad adottare diverse tecniche tipicamente ingresiane per affrontare e risolvere alcuni problemi formali nella resa delle figure. (3)

Un esempio: Seated man (1939) richiama chiaramente il ritratto di Ingres di Philibert Riviére (1805) nella difficoltà della posa e nelle gambe accavallate.

“Gli uomini di de Kooning “spesso basati su autoritratti realizzati con l’aiuto di fotografie o di specchi nel suo studio, di un manichino costruito da lui stesso e di studi dei propri amici e vicini, come il poeta a critico di danza Edwin Denby e il fotografo Rudolph Burckhardt, sono anonimi, austeri e isolati. Sono dipinti in profondi toni caldi con contorni indefiniti e una combinazione di allusioni alla storia dell’arte, al modernismo, e alla quotidianità.

Spinto in parte dai coevi dipinti con figure di Gorky, de Kooning successivamente parlò degli “uomini” come di ritratti immaginari alla maniera di Ingres e dei fratelli Le Nain (Roadman 1961 p 103)”. (4)

Ecco un’altra sorpresa: emerge in Two standing men e nel Ritratto di Rudolph Burckhardt un riferimento all’opera dei fratelli Le Nain. L’attenzione si concentra interamente sull’abilità nel rendere pittoricamente gli indumenti. Il critico Jed Perl nel suo New Art City: Manhattan at Mid-Century approfondisce, nel capitolo intitolato “The Philosopher King”, l’opera di de Kooning, evidenziando questo influsso solitamente meno analizzato.

Ma è nei tardi ritratti di Cézanne che possiamo trovare l’origine di quell’inespressività che si carica di silenzio, tipica dei volti degli uomini di de Kooning.

“Nonostante egli fosse chiaramente influenzato da Cézanne abbastanza presto, un influsso diretto non entrò in gioco, nei suoi dipinti, prima del 1938 circa, anni dell’amicizia con Gorky. Chiari esempi di questo ascendente possono ritrovarsi nelle opere Two men standing del 1938 e nel Vetraio del 1940. Le pieghe dei pantaloni del soggetto sulla sinistra di Two men standing ostentano un notevole tentativo di appiattire l’immagine e di mostrarne, al tempo stesso, la profondità, mentre il torace delle due figure è modellato similmente, usando superfici piatte di colore. L’influenza di Cezanne è perfino più ovvia nel Vetraio: l’uso di superfici piatte di colore è funzionale a rendere tradurre le pieghe della tovaglia e le grinze dei pantaloni della figura”. (5)

Anni dopo de Kooning avrebbe ricordato così la sua genesi.

“Presi i miei pantaloni, quelli da lavoro. Feci un miscuglio di acqua e colla, vi immersi i pantaloni e li asciugai davanti al calorifero, poi, ovviamente dovevo togliermeli. Li ho sfilati: avevano un’aria così patetica. Ero commosso; ho visto me stesso lì in piedi. Mi sentivo così dispiaciuto per me stesso. Poi ho trovato un paio di scarpe — da uno scavo — coperte di cemento, e le ho posizionate sotto. Tutto sembrava così tragico che mi sentivo sopraffatto dall’autocommiserazione. Quindi gli ho infilato una giacca e dei guanti. Ho modellato una piccola testa in gesso. Ne ho fatto dei disegni e per anni l’ho tenuto nel mio studio”. (6)

La pittura di de K non ricerca il sublime, al contrario, ha una vicinanza fisica alle cose. Come se rappresentasse l’esperienza della realtà facendola coincidere con l’esperienza della pittura. Ecco spiegata anche la sua apertura nei confronti del kitsch e della cultura di massa.

“L’arte non mi rende mai sereno o puro. Mi sembra di essere avvolto nel melodramma della volgarità. Io non penso … all’arte come ad un situazione confortevole”.(7)

Molti anni dopo, de Kooning avrebbe ricordato quegli anni:

“Ho distrutto quasi tutti I dipinti di quel periodo, avrebbe detto più tardi a Selden Rodman. Vorrei non averlo fatto. Allora ero così modesto da rasentare la superficialità. Alcuni erano validi, una parte del reale me stesso. Proprio come i Mangiatori di patate (un grandioso dipinto giovanile di una famiglia di contadini) di Van Gogh è un buon lavoro, allo stesso livello di tutto ciò che egli dipinse successivamente nel suo caratteristico stile”. Le opere di quel periodo sono sopravvissute per lo più per caso: furono infatti acquistate o rimosse dallo studio prima che egli le distruggesse. (8)

Emerge in questa affermazione la natura mercuriale dell’artista, il suo moto perpetuo, il fare e disfare l’opera secondo la splendida lettura che ne ha dato recentemente Jed Perl.

“Willem de Kooning appare come l’archetipo del moderno uomo urbano. Egli è a volte arrogante, altre sensibile. È nevrotico, sicuro di sé, irruente, mercuriale. È un cercatore, un combattente, un commediante, un seduttore, un sognatore. Questo repentino cambiamento di personalità emerge innanzitutto attraverso la straordinaria varietà di tocco di de Kooning, che in una singola opera può spaziare dal raffinato al tirato via, da intrecci delicati a colpi sferzanti. L’ampia gamma dell’artista si percepisce in quell’enigma che sono le sue creazioni: a volte opprimenti labirinti, altre disorientanti finali aperti, spesso progettate con lo scopo di negare ogni definizione. Pure, si nota il costante cambiamento cui il suo lavoro si sottopone, perfino per brevi periodi, dalla messa a fuoco della figura, ad un soggetto più insistentemente astratto o alle suggestioni di un paesaggio. De Kooning è uno che prende delle decisioni e poi ci ripensa, ancora e ancora”. (9)

(1) Roberto Pasini L’Informale. Stati Uniti Europa Italia. Clueb Bologna 1995 p. 103

(2) Citato Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler , mercante tedesco, collezionista, scrittore, in Huit entretiens avec Picasso, Le Point, Mulhouse, n°XLII, oct. 1952, p. 22-30

(3) Lader, Melvin P. Graham, Gorky, de Kooning, and the ‘Ingres Revival’ in America. Arts Magazine. 52, no. 7 (March 1978): 94-99.

(4)SusanF.Lake, Willem de Kooning: The Artist’s Materials p. 8

(5) Herrera, Hayden. Arshile Gorky: His Life and Works. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York: 2003 p. 138 quoted in Lauren Foster, Arshile Gorky’s Influence on the Early Paintings of Willem de Kooning Senior thesis, 2006, MontclairStateUniversity.

(6) Sally Yard, Willem de Kooning: Works, Writings and Interviews, July 1st 2007, Ediciones Poligrafa S.A. p.21

(7) Robert Motherwell, Beyond the Aesthetic, Design 47, April 1946, as quoted in W.C, Seitz Abstract Expressionist Painting in America, Cambridge Massachusetts, 1983, p. 101

(8)Stevens, Mark, and Annalyn Swan. de Kooning: An American Master. New York, Knopf, 2004, p. 141

(9) Jed Perl “The Abstract Imperfect” in The New Republic November 3, 2011